Russia’s answer to James Bond: did he trigger Putin’s rise to power?

English-Russian

He was a brooding spy whose adventures gripped 80 million viewers every night – including President Brezhnev. But did Max Otto von Stierlitz also inspire Putin?

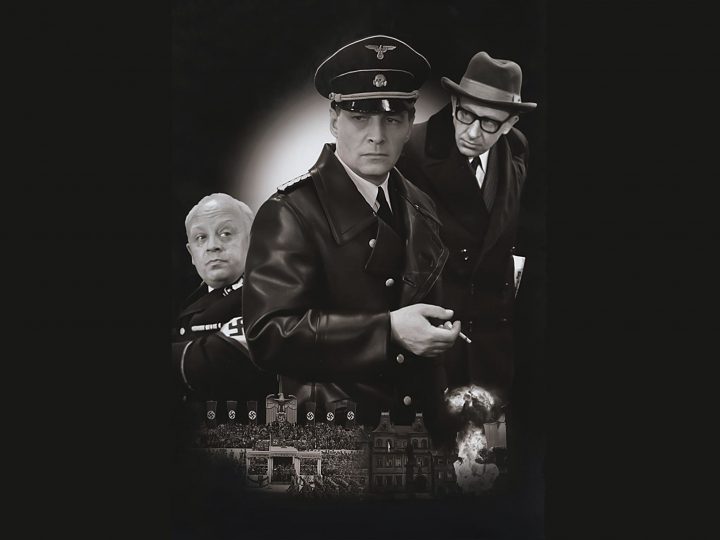

On 11 August 1973, a TV series was premiered throughout the Soviet Union that stopped the people in their tracks. Seventeen Moments of Spring was broadcast at 7.30pm over 12 consecutive nights, and this black-and-white second world war spy drama amassed an astonishing 50 to 80 million viewers per episode.

For the 70 minutes of each show, city streets emptied, power station output surged and crime halted. Leonid Brezhnev, the Soviet leader, apparently changed the time of Central Committee meetings in order to catch every episode, so addicted was he to this slow-burning tale of a Soviet spy who infiltrates the Nazis in order to foil Operation Sunrise. That was the name given to the real-life secret negotiations between German and American intelligence, which aimed to forge a separate peace in the dying months of the war.

“I don’t remember a time when I wasn’t aware of this series,” says Dina Newman, a journalist with the BBC World Service who was born in Moscow. “It came out when I was eight. It’s something I grew up with. Everybody at school talked about it. It quickly became part of our cultural experience, our folklore.”

Like so much Soviet cultural output of the 70s, Seventeen Moments began as propaganda, part of the reforms initiated by Yuri Andropov, the recently appointed head of the KGB, to improve the security agency’s image.

“Andropov felt the KGB’s authority had been damaged by Nikita Kruschev’s de-Stalinisation reforms,” says Newman. “He wanted to bring prestige and mystique back to the work of secret agents, in the hope of attracting educated, young recruits.”

Andropov commissioned a series of books, songs and films to glorify the work of agents serving abroad. One was a piece of detective fiction by Yulian Semyonov. “Andropov had read Semyonov’s earlier novels,” says Jeremy Duns, an espionage expert and writer of spy novels. “He opened the KGB archives to him – including the classified files on Operation Sunrise.”

Written in just two weeks, Seventeen Moments was commissioned as a TV series before it had even been published, under the guidance of one of the few female Soviet directors, Tatyana Lioznova. She was “assisted” by Andropov’s deputy and two KGB operatives brought in as “technical advisers”. Despite these incredibly restrictive conditions, Lioznova transformed propaganda into art, bringing in the brooding, handsome actor Vyacheslav Tikhonov to play the show’s double-agent hero, Max Otto von Stierlitz.

Her other masterstroke was to commission the Soviet composer Mikael Tariverdiev to write the series’s score, which went way beyond atmospheric backdrop. “Tariverdiev’s music brings out Stierlitz’s inner life,” says musician and producer Stephen Coates. “One of the reasons it appealed to Soviet audiences at the time is its themes of loss and separation.”

Coates has been a fan of Tariverdiev’s music since he first heard it in a Moscow cafe seven years ago. “Haunting, poignant and magical – it blew me away,” he says. “I got in contact with his widow, Vera, and we became friends.” Coates is now reissuing Tariverdiev’s works through the Earth Recordings label, and has organised a marathon screening of a subtitled Seventeen Moments at Pushkin House, London, this month.

“One reason the series still stands up,” he says, “is that it retains an undercurrent of fear, of people being watched. In showing Hitler’s Germany, it was actually depicting Russia. People go about their business, but they’re never really free.”

“Mikael wasn’t too thrilled about working on a spy series,” says Vera. “But he was intrigued by the possibilities. The plot required a continual musical theme. He agreed to work on the project only after finding the answer to that. He was introduced to an intelligence agent and discovered the details of his romantic inner life, which was nostalgia, the longing for a distant homeland.”

There is a memorable six-minute scene in Seventeen Moments where Stierlitz and his wife meet in a German cafe. Not a word is spoken: there is just Tariverdiev’s mournful piano theme. The scene is based on real events. Soviet agents working abroad would be taken to see their loved ones, but couldn’t communicate with them. It was a demonstration of control: “We have her, she’s alive, stay loyal.”

The scene, says Dina Newman, “went straight to the heart of the Soviet people. There is a coldness to the series. Much of its running time is taken up with wartime archive footage the Soviet army commandeered from the Germans. But its emotional side is carried by Tariverdiev’s music. It became an aspect of Stierlitz’s character. In this soulless world, it gave him a soul.

“The main song, Moments, is based on a poem by Robert Rozhdestvensky about how each moment in life has profound significance. You could interpret it as being about the life of a foreign agent but it was written about life under a dictatorship, where any moment you could lose your position, your life, or betray someone and be promoted. It’s a philosophy born of Soviet life.”

From that first broadcast Stierlitz became something of a Soviet folk hero, the anti-James Bond. “He’s a response to how the KGB was depicted as Smersh in the Bond films,” says Coates. “He’s very different from Bond. He spends more time gazing through windows than crashing through them. There’s a lot of smoking, a lot of being haunted by the motherland.”

“I’d be fascinated to know if John le Carré has seen Seventeen Moments,” says Jeremy Duns. “Stierlitz is more like George Smiley than a Russian James Bond: a methodical, unemotional guy who silently observes while everyone else is digging their own grave.”

Every year, the series was rebroadcast throughout Warsaw Pact nations on 9 May, the holiday that commemorates the surrender of the German army in 1945, and Stierlitz jokes became common currency, sending up the actor Tikhonov’s humourless, deadpan delivery. Yet the show did help to increase the Soviet people’s faith in their secret services, advancing the belief that the USSR had single-handedly won the war.

The series had a curious afterlife in the chaos that marked the dissolution of the Soviet Union. In 1991, a St Petersburg film-maker made a short film about a local councillor, who’d previously worked as a Soviet spy in East Germany. One scene re-enacted the ending of Seventeen Moments, when Stierlitz drives back to Berlin. The councillor was filmed behind the wheel of his GAZ Volga with Tarivadiev’s Seventeen Moments theme, Somewhere Far Away, playing in the background.

The councillor was Vladimir Putin. “It stuck,” says Newman. “People began to associate Putin with Stierlitz. Putin never said directly whether Stierlitz inspired him to become a spy. But he was 21 when the series was first screened and he joined the KGB two years later.”

The association certainly didn’t do Putin any harm. In 1999, an opinion poll in the Kommersant newspaper asked readers who they’d like to see as Russia’s next president. Stierlitz came second, next to Marshal Zhukov, the Soviet Red Army general. The cover of the newspaper’s weekly supplement carried a picture of Stierlitz with the caption: “President – 2000.”

“It proved that the second world war remained Russia’s highest point of achievement,” says Newman, “with military force still hugely respected. The previous president, Yeltsin, was boozy, jokey, generous. Now people wanted somebody a bit less Russian.”

Amid the dishonesty and corruption of late-90s Russia, Putin stood apart – in no small way because he was seen as a Stierlitz-type figure. “Power should be mysterious and magic. Especially in Russia,” his former adviser, Gleb Pavolvsky, told Vanity Fair in October 2000. “Putin answers that need perfectly.”

Eighteen years on, there can be few Russians who still think of Putin as Stierlitz, but the series remains ingrained in Russian culture. “Everybody still knows Seventeen Moments, even teenagers,” says Vera. “They’ve forgotten the name of the author, but the series? Yes, they all know it well.”

Британский кинокритик Эндрю Мэйл объявил сериал «Семнадцать мгновений весны» причиной, по КОТОРОЙ к ВЛАСТИ Пришёл Президент России Владимир ПУТИН.

Об этом он написал в The Guardian во вторник, 11 сентября.

Мэйл считает, что двенадцатисерийный телефильм Татьяны Лиозновой был создан по заказу КГБ и был призван повысить престиж работников комитета, в том числе разведчиков, и привлечь в орган новых людей.

Главный персонаж сериала, штандартенфюрер Макс Отто фон Штирлиц, советский разведчик, стал, по мнению кинокритика, героем в СССР, а анекдоты про него — частью советского фольклора.

Мэйл добавил, что после распада СССР фильм «Семнадцать мгновений весны» получил «любопытное продолжение». В 1991 году петербургский режиссер выпустил короткометражную ленту о местном политическом деятеле, который ранее служил разведчиком в Восточной Германии. Этим человеком был Владимир Путин.

Одна из сцен короткометражки повторяла концовку сериала Лиозновой. «И это привязалось. Люди начали ассоциировать Путина со Штирлицем. Путин никогда прямо не говорил, вдохновил ли Штирлиц его на то, чтобы стать шпионом. Но ему был 21 год, когда вышел сериал, и он поступил в КГБ через два года после этого», — цитирует автор статьи журналистку Дину Ньюман.

Мэйл также напомнил о номере газеты «Коммерсантъ» 1999 года с опросом для читателей — кого бы они хотели видеть следующим президентом России. На втором месте оказался Штирлиц, его же фото поместили на обложку еженедельного вложения с подписью «Президент-2000».

Автор сделал вывод, что приход Путина к власти находится в определенной связи с народной любовью к Штирлицу и к тому, что Путина ассоциировали с персонажем. Однако он отметил, что сейчас в России мало кто продолжает видеть это сходство.

«Как научить себя учиться» Введение в Систему Михаила Шестова

«Как научить себя учиться» Введение в Систему Михаила Шестова Основополагающие постулаты освоения английского языка

Основополагающие постулаты освоения английского языка О чем никогда не расскажет репетитор английского. Секреты профессии

О чем никогда не расскажет репетитор английского. Секреты профессии Пара смешных проблем в изучении английского

Пара смешных проблем в изучении английского Лео Бокерия и Михаил Шестов: КОВИД и ИНСУЛЬТ лечатся ЧТЕНИЕМ ВСЛУХ

Лео Бокерия и Михаил Шестов: КОВИД и ИНСУЛЬТ лечатся ЧТЕНИЕМ ВСЛУХ

Карпов Александр

Поначалу сомневался, т.к. произношение у меня было поставлено. Но потом, разобравшись в методе, компетентность автора стала очевидна, и те «сектора», в которых были проблемы, пришли в норму. Усвоив метод, я понял, что могу выучить любой язык, который мне понадобится. Огромное человеческое спасибо Михаилу Юрьевичу и сотрудникам!